“Where is the Jungfrau?” Mylord and Mylady struggle to navigate the Swiss mountains.

Deutsches Tagebucharchiv

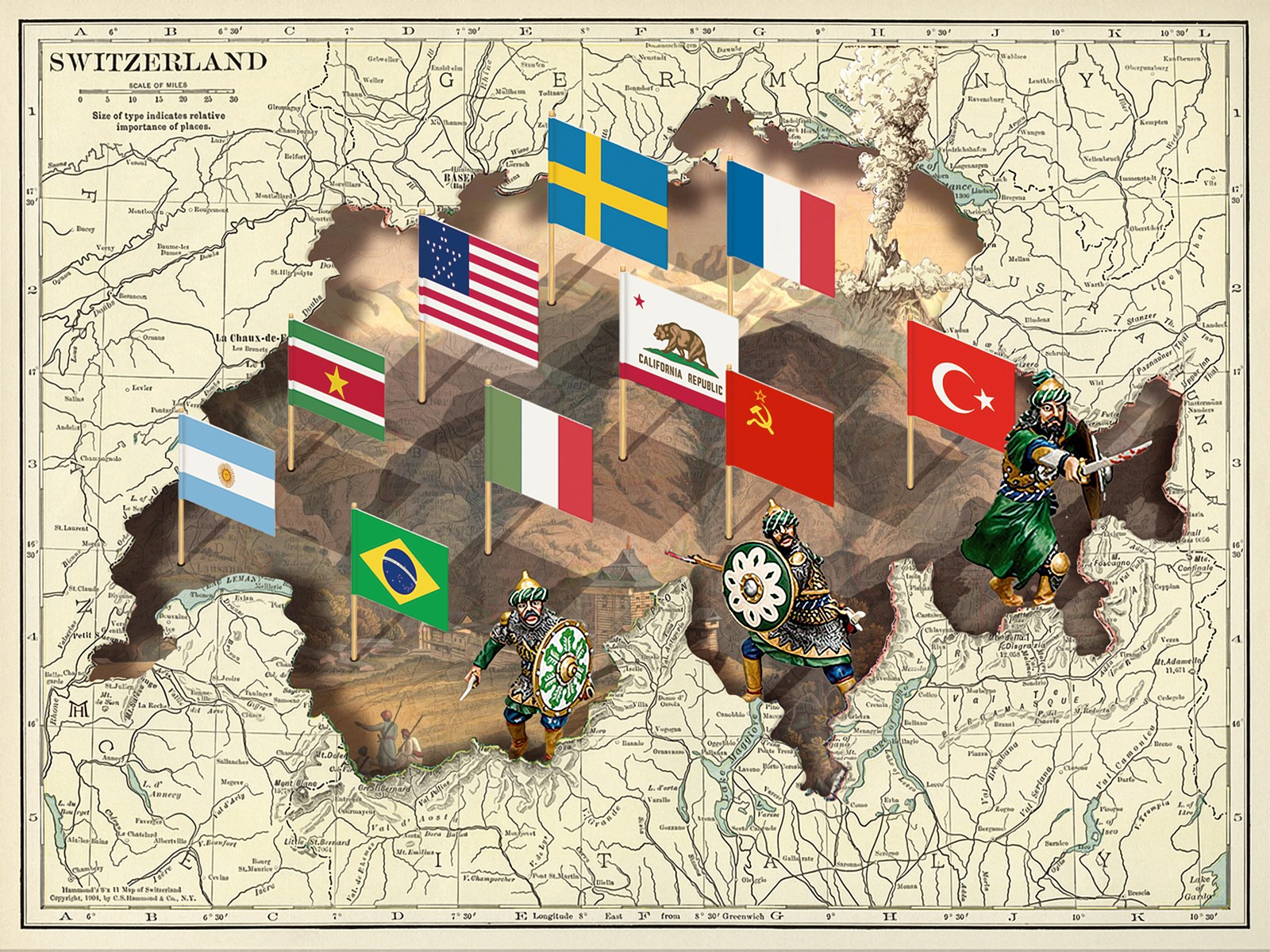

German theologian Carl August Wildenhahn documented his journey through 19th century Switzerland with humorous observations and comic strip-style pictures.

In the early summer of 1837, Carl August Wildenhahn set off from Dresden by stagecoach to travel through Switzerland and to finally see for himself the land of his dreams with its “eternal glaciers and graceful Bernese girls”. Wildenhahn documented his three-week trip with amusing anecdotes and comic strip-style illustrations.

This article External linkwas originally published on the blog of the Swiss National Museum on February 9, 2023.

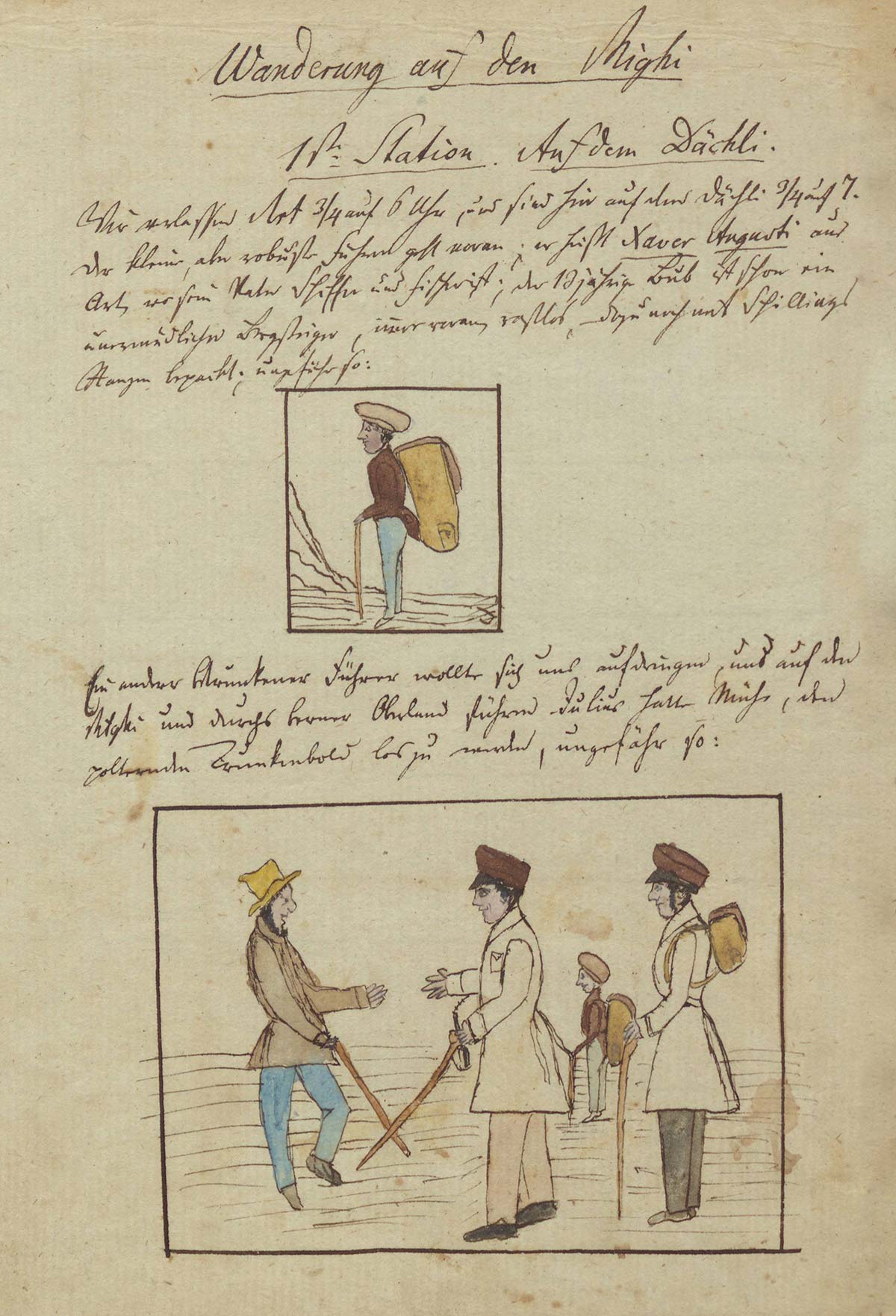

“We left Art[h] at a quarter to six. The small yet sturdy guide led the way. His name is Xavier Augusti, and he is from Art[h], where his father is a boatman and fisherman. Xavier is 13 years old and already an indefatigable mountain climber, always marching off ahead, absolutely tireless.

First, the path takes us through Goldau – the village that was buried by an avalanche in 1806 and still bears the scars of the devastation – before leading straight uphill. Large beads of sweat were soon pouring off my forehead. A few shepherd’s huts came into view – making for a very quaint scene. We made a brief stop at an inn perched on the rocks like an eagle’s nest called the Dächli in order to enjoy some kirsch refreshment – which according to our little friend Xavier tasted passable.

While we were there, we saw some black and brown goats climbing down a rock face so steep it could make you feel dizzy. It’s already 7 o’clock and we still have 3 hours left to climb if we want to reach the summit today.”

With comic strip-like illustrations, Wildenhahn also provides a visual insight into his journey through Switzerland.

Deutsches Tagebucharchiv

The ascent of the Rigi is a particularly amusing chapter in Wildenhahn’s travel journal, in which he encounters some “curious” characters and in passing paints a surprisingly accurate picture of early Alpine tourism.

“Monday morning, 7 o’clock. This is the starting point for the four stations on the pilgrim path that leads to the monastery, also known as the Rigi Klösterli. It is very busy. Ahead of us there are several smaller and larger groups, in which we can’t help but notice a woman climbing past the stations in pious haste, stopping at every one to kneel and pray.”

The theologian from Dresden met many pilgrims climbing the pilgrim path in “pious haste”.

Deutsches Tagebucharchiv

“Xavier could surely tell us all about these things but we can hardly understand a word he says as he speaks a very thick Swiss German dialect. The ninth station is enough to make pregnant women miscarry and criminals confess. If one looks through the bars into the semi-darkness of the chapel, one is met with a fiery stare – belonging in fact to the semi-prostrate Christ with a pair of glassy eyes, carrying the cross.

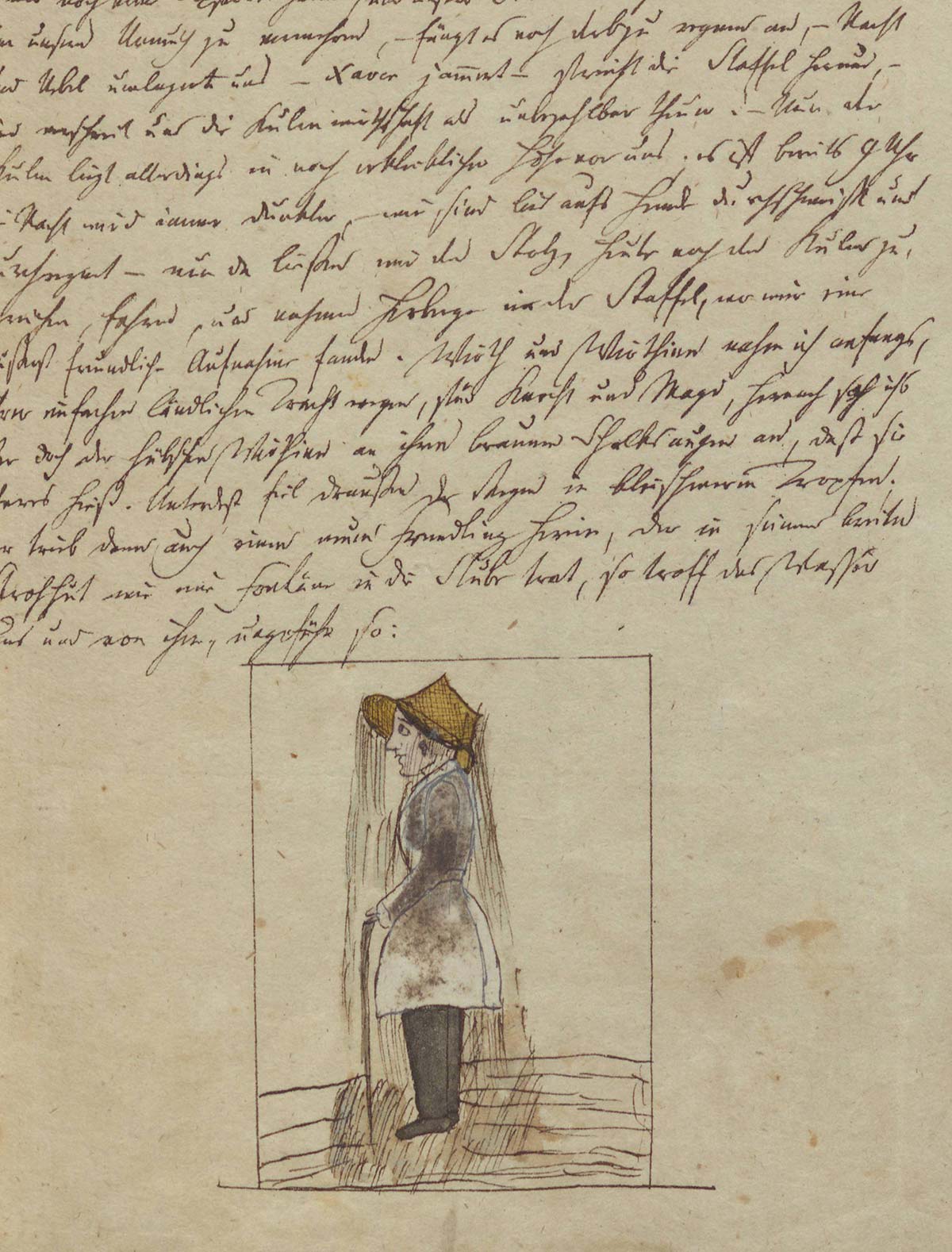

At his side, a weeping Mary, a smirking Jew, and an executioner’s assistant wielding a whip. They are all crude, hideous, painted wooden figures that are bigger than life size. If the moonlight caught that scene as a peaceful walker happened to be passing by, it would scare the life out of him. And to make matters worse, it started to pour with rain. We were besieged by darkness and fog. We took shelter at the Staffel inn where we received an extremely warm welcome.

Meanwhile, the rain fell outside in leaden drops. At that moment, a stranger walked into the restaurant looking like a fountain in his wide straw hat with water pouring off it…”

A soaking stranger turns up at the restaurant.

Deutsches Tagebucharchiv

“Incidentally, the new arrival was a charming and friendly man, a young doctor from Liechtensteig in St. Gallen, who had already climbed the St. Gotthard in April to visit a patient with a respiratory disease. We dined together and enjoyed the Markgräfler wine – which lifted our spirits and loosened our tongues – until eleven in the evening.

At ten o’clock the next morning, the clouds parted, affording us a wondrous view of Lucerne, Schwyz and Zug. The pleasant towns and villages resemble specks of light on the green expanse. Everything looks as if it is within touching distance, and so perfect that it could be a painting. Seeing God’s natural world in all its splendour and glory is a truly humbling and edifying experience.We were re-energised and within half an hour reached the summit (Rigi Kulm), where we got a friendly reception at the neat little inn. But there was little talk of the view – everyone was more interested in what was going on inside.”

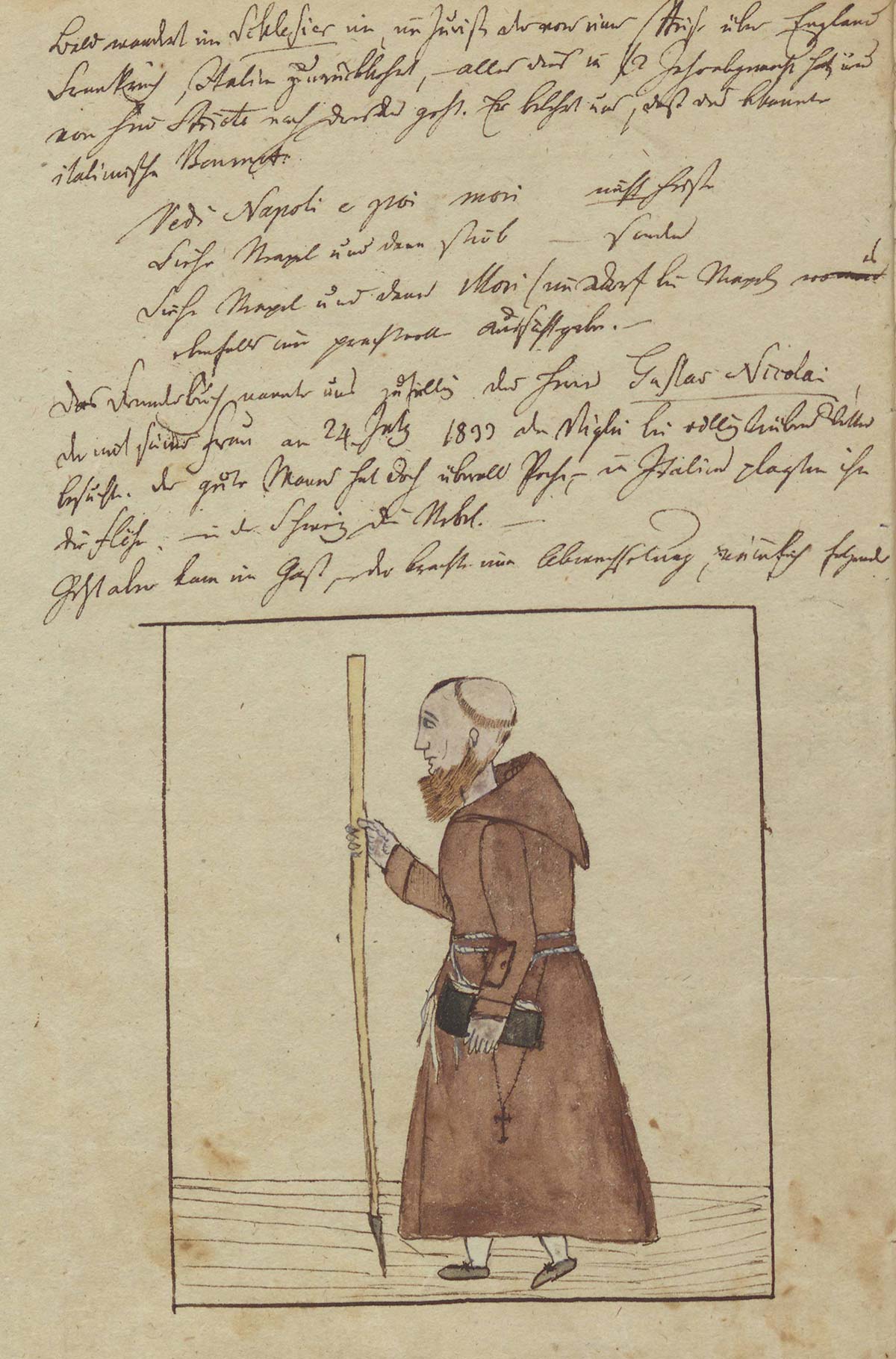

“We came across a large room with three young men: one from Boston and two from Zurich. They had spent the night here and not enjoyed it much. But then came a guest who brought some diversion.

A Capuchin monk – a tall, thickset man wearing a brown robe, a white cord at his waist, a blue snuff handkerchief in his cowl, and in his sleeve pocket a tin of snuff which he busily inhaled without offering any around. He is the Father Superior at the monastery – he carries his Breviary around with him and enjoys the worldly pleasures of coffee, wine, bread and cheese that the Lord has bestowed upon him. I conversed with him in Latin, which he seemed to struggle with, but we managed. I offered him a cigar – which he refused. He told me nobody else in the monastery smokes either, although it’s not forbidden.

On the Rigi Carl August Wildenhahn also met a Capuchin monk. The pair “conversed” in Latin.

Deutsches Tagebucharchiv

He tells us how in the winter there are only two monks left in the monastery, while in summer there are six to eight. The innkeeper here is called Bürgi – a quiet, rather squat man, while his wife Lisette is a pretty young thing wearing traditional Swiss dress. She had previously lived for some time in Dresden – where she had long been deceived by an unfaithful husband – and now lives happily at the top of the Rigi, although by all accounts she is happier in her waking hours than at night.

I initially mistook the waitress here – a pretty young girl – for the landlady, to which she replied, blushing: “Forgive me, sir, but I’m not the boss”. – Now an Englishman appears with his wife. They have been here for three days waiting for good weather; he has a proper ruddy English complexion and wears a long Mackintosh with silver coin-like buttons and carries a guidebook.”

There is something comedic about the time on the Rigi. While the Latin-speaking monk explains why he doesn’t smoke, an Englishman waiting for better weather suddenly disappears into the thick fog…“And then an eccentric idea came over him and he rushed out into the foggy night. The woman and guide followed him; but at the point marked by a cross – the most dangerous spot, where one false step means a 5,600 feet drop – he disappears. The fog makes it impossible to search for him. The guide calls out: ‘Mylord, where are you? Come up, please, don’t go down there! It’s dangerous!’ No answer. The woman glances briefly down the steep slope. Mylord has disappeared.I’m filled with terror – what will Mylady do? She smiles and returns to the inn with the guide. Finally, after half an hour, Mylord crawls back up. I couldn’t wait to see their joy at being reunited. I accompany him into the building, where Mylady is sitting on the sofa, reading. Mylord comes in, no greetings, no questions. No one looks at each other. The guide shakes his head. What strange people, the English! Like everywhere in Switzerland, the coffee here is bad, but the milk is better, which is why coffee is always served so milky. The library at the summit comprises most of the best French and German classics of fiction.”

Why the Jungfrau is called Madame Meyer

“And now for the view from the top of the Rigi. The fog slowly clears to gradually reveal the landscape: to the west Lake Sempach, Lake Hallwil and Lake Baldegg, interspersed and overshadowed by small mountain ranges with open meadows delightfully enclosed by trees, and not a sowed field in sight. To the east: Lake Zug in all its glory, Lake Ägeri and Lake Lauerz with the ruins of Goldau, a glimpse of Lake Zurich, and further afield, the snow-capped Appenzell Alps, and to the south, the magnificent Alps of Schwyz, rising like a mythical grandfather.

Below and above, the Uri Rotstock and the Stanserhorn come into view. But the Bernese Alps are still shrouded in cloud – and it is only possible to make out their contours. One of the guides joked that the previously untouched Jungfrau (which means ‘virgin’) was to be called ‘Madame Meyer’ after Johann Rudolf Meyer and his brother Hieronymus climbed it for the first time.

Next to us stands the Englishman, the wide flaps of his fur cap folded down, map in hand, and next to him the guide, who has to accompany the Englishman everywhere to explain everything as he gesticulates into the air with his umbrella. Mylady stands nearby, shivering with cold. She clutches at her hat with both hands, pacing back and forth as a strong, cold wind blows, while carrying her alpenstock under her arm.”

More

More

Newsletters

“Where is the Jungfrau?” Mylord and Mylady struggle to navigate the Swiss mountains.

Deutsches Tagebucharchiv

“As the sun appears from behind the clouds, the guide points at it with his umbrella: ‘Mylord and Mylady, that’s the sun you can see over there!’ – ‘Oh yes – the sun’ – replies Mylady, cursing a ‘goddam’ at the wind, as a strong gust leaves her revealing rather more than she would have liked. Meanwhile, Mylord turns to look at the map of the mountains, whereupon the guide has to show him in which direction the sun sets. Frozen through, we savoured a copious supper, consisting of soup, potatoes and butter, pike with sauce, chicken pie, roast veal with salad, roast beef with sauce, apple pudding, and all sorts of confectionery, nuts, preserves and tarts. One needs to have the appetite of a Swiss to eat all that!

The excitement about seeing the sunrise got me out of bed at 3 o’clock the next morning. Before long, Mylord and Mylady who – as we discovered last night are actually American English, appeared with their guide, chatting away cheerfully as they walked, despite the cold. I can’t overstate the beauty of the scene that awaited us: the sun appeared in all its glory, its rays illuminating the silver white Alps of the Bernese Highlands. The sublime Jungfrau and its vast neighbours looked calmly into the sun’s face until their snowy cheeks blushed with shame. How fortunate we are – more so than Mylord, who despite the guide’s explanations, is still trying to make out the Jungfrau.”