A scene from Jean-Luc Godard’s 1966 film “Masculin-Féminin”. In the watch industry, the traditional focus on masculine needs could be changing.

1966/Columbia Pictures

Fashion is increasingly distancing itself from gender stereotypes and obscuring the line between male and female. Swiss watchmakers too are having to choose whether or not to maintain the traditional division between men’s and women’s styles.

“A watch for Sylvester Stallone wouldn’t do for Audrey Hepburn,” says designer Bruno Bellamich, co-founder of the brand Bell & Ross. “Not because of some male or female fashion ideal, but simply because of the difference in wrist sizes of these two American stars.”

Bellamich, however, is not taking into account the resistance that has accompanied all fashion revolutions. Think of Coco Chanel, who used to borrow items from the male wardrobe and didn’t like small watches for women. Of course, in Coco Chanel’s day, men’s watches were of the size of women’s timepieces now.

A Luminor Submersible 1950 watch, worn by Sylvester Stallone in “The Expendables 2”, up for auction at Sotheby’s in New York, June 2024.

Keystone/epa

As for Stallone, these days he would have to content himself with a smaller model. The extra-large timepieces that were fashionable in the 2000s have disappeared. The trend is no longer one of exaggerated masculinity, much less a caricature of it.

Can a watch be sexy?

A Royal Oak model by Swiss brand Audemars Piguet, which belonged to former Formula 1 star Michael Schumacher, at Christie’s auction house in New York, May 2024.

AFP or licensors

When Julien Tornare was head of Zenith, the famous watch brand from Neuchâtel in western Switzerland, he used to say he wanted to abandon ostensibly “male” watch models. “That kind of division has gone in the automobile industry,” he said, “and it will disappear in watchmaking too.”

Now he is pursuing this strategy at TAG Heuer. Ricardo Guadalupe, who heads the Hublot brand, shares this view. “Although we happen to have a higher proportion of male customers,” he declares, “we have stopped classifying watches by gender. We have different collections with a range of sizes, offering a diversity of choice.”

As well as unisex watches and a more targeted specialised range, brands now want to express the idea of freedom of choice in their marketing. Cyrille Vigneron, the CEO of Cartier, recalls that in the early days of watchmaking there were no models that were specifically women’s or men’s – they simply became “female” or “male” depending on the person who owned them.

He believes the age of strict separation of styles is over, and that watchmakers should no longer be imposing their own preferences. “It’s not our job to determine who is to wear a particular Cartier watch,” he says. “Our job is to give people freedom of choice, and make the choice as wide as possible.”

A platinum watch for women by Bulova.

Rene Paik/Alamy Stock Photo

Other representatives of mainly “women’s” brands are not so enthusiastic about this idea. “I really don’t have much time for this movement towards sexless watches,“ says Antoine Pin, managing director of watches at Bulgari. “Is this supposed to mean a watch can’t be sexy?”

The collections for men represent a small proportion of the products of brands such as Chanel, Harry Winston, Dior and Chopard. Catering mainly to a female clientele, these watchmakers do not need to bother with creating unisex models that would also suit men.

Diamonds, not complications

For many years, watches for women were made according to a rather cynical formula. They were produced much like those for men, but smaller, with a quartz movement instead of a mechanical one, and set with diamonds.

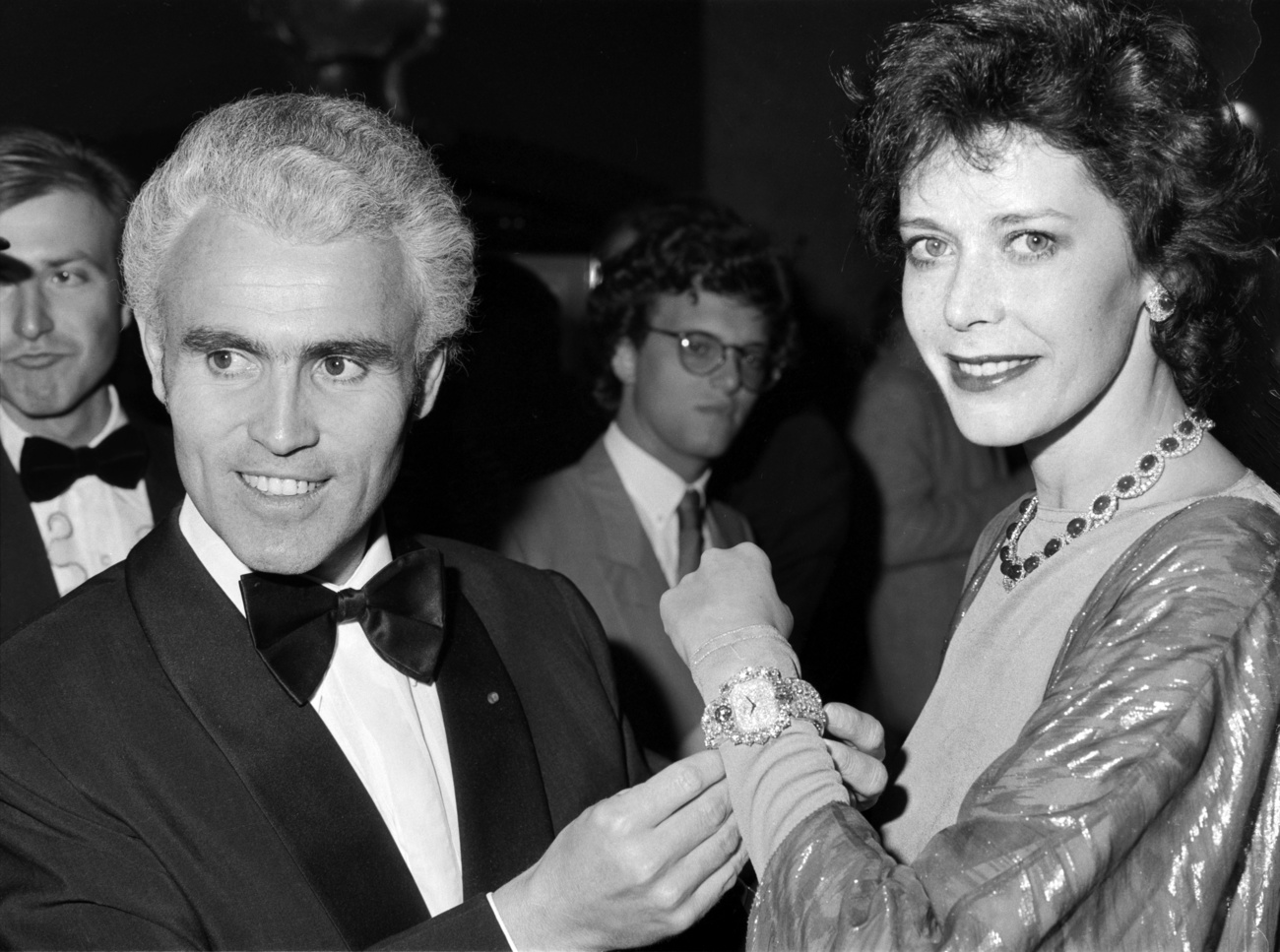

Actress Sylvia Kristel (right) and Swiss watchmaker Yves G. Piaget showing off a glittery model in St Moritz, 1982.

Keystone

The idea at the outset was that women didn’t need particular watch functions or so-called complications – with the possible exception of moon phases – beyond telling the time. Furthermore, women didn’t like the idea of winding a watch and preferred a battery, it was thought. Smaller models also had less room in them for complications. Diamond decorations compensated for the simplicity of the technology.

The Grand Prix de l’Horlogerie de Genève (GPHG), a major prize in the Swiss watch industry, is awarded in the categories of watches for men and watches for women, with or without additional functions. The introduction, in 2013, of a “ladies’ complication watch prize” was a turning point.

Want to read our weekly top stories? Subscribe here.

Fairies, flowers and birds

But the issue of which complications are wanted remains open. In 2010, Van Cleef & Arpels launched a complex mechanical watch, called Pont des Amoureux, featuring an animation representing two lovers meeting on a bridge. “We had to forget the fact that a watch complication is for precision, and just focus on the aesthetic value of the piece,” explains Nicolas Bos, who was CEO of the brand from 2010 to 2024.

The watchmakers of Van Cleef & Arpels even invented a new category called “poetic complications”, opening the way to all sorts of creations where flowers bloom, birds flap their wings and fairies wave magic wands.

At the last GPHG awards ceremony, the “ladies’ complication watch prize” drew an objection from one member of the jury, the Scandinavian watch connoisseur Kristian Haagen. “A complication is a complication, so why do we need different categories of complications for women and men?” he asked.

Tiny tourbillons

Haagen may have been right in thinking that “poetic complications” might express an unspoken doubt about women’s ability to appreciate technology without a romantic façade. This type of technology is used purely as a decoration, which is questionable for any purist among watchmakers.

Yet in fact, even traditional watch complications have lost their utility. At one time, the mechanism known as the tourbillon was meant to compensate for the effects of gravity in the mechanism of the watch and ensure accuracy. The complication known as “minute repetition”, meanwhile, was created to tell the time in darkness. Today, even with mobile phones that give the exact time, the beauty of the challenge to the traditional watchmaker remains.

Bulgari’s iconic Serpenti Seduttori model.

Bulgari

“The tourbillon is no longer of any practical value, but it is still a triumph of the watchmaker’s art,” says Jean-Christophe Babin, CEO of Bulgari, which has included miniature tourbillons in its iconic Serpenti models. “So women can legitimately wear this ‘diamond’ in our watches.”

Growing customer segment

Today women represent a growing proportion of the clientele for luxury watch brands. They are guided by their own tastes and their own understanding of what a “lady’s watch” should be.

According to Chrono24, a platform specialising in the sale of luxury watches online, the proportion of women who bought luxury watches with a diameter of at least 40 mm grew from 21% to 35% between January 2019 and December 2023. The results of their study feature another interesting fact: women represent 59% of the total clientele for watches in the price range between €10,000 and €20,000 (CHF9,700-CHF19,400).

In an article in Chrono24 Magazine, journalist Elisabeth Schroeder notes that “women are more open to watches with an unconventional shape, such as rectangular, square, etc.” This would indicate their boldness as consumers, in contrast with men, who tend to prefer round watches.

Women at executive level in the industry

Yet the key to making the watch industry more inclusive and less prone to stereotypes is perhaps to be found elsewhere. Whereas today women buy their own watches, these are still mostly designed and produced by men. “In the watchmaking world, only 17% of the top jobs are held by women,” notes the Swiss watch industry employers’ convention (CPIH).

Women in a watchmaking factory in Besançon, France, in 1908.

AFP/Jacques Boyer

However, Marine Lemonnier-Brennan, founder of the agency 289 Consulting, can see a shift in this male-dominated world. “In the last few years, we have seen women moving into strategic jobs with Jaeger-LeCoultre, Chopard, Audemars Piguet, Vacheron Constantin, Hublot, TAG Heuer and Harry Winston,” she says. “They are CEOs, product heads, designers or managers of movements, and they are contributing to making watchmaking evolve towards a product offer designed for and aimed at women.”

She cites as an example the Beauregard brand, founded in Geneva by Alexandre Beauregard in 2011, which from the start aimed to create watches combining jewellery and complex mechanisms. “Never before was an independent brand of high-end watches created solely for women,” she says.

Edited by Samuel Jaberg. Adapted from French by Terence MacNamee/gw