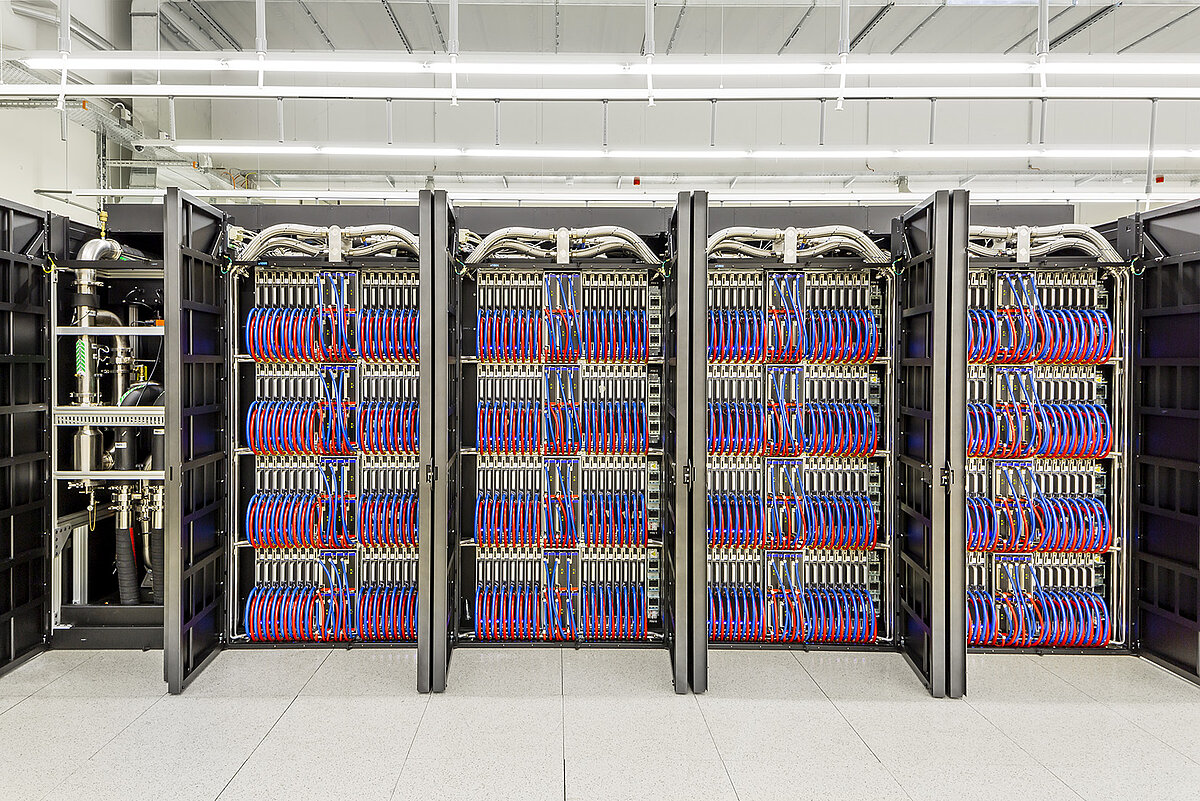

The Alps supercomputer in Switzerland is the world’s sixth most powerful machine.

Marco Abram, CSCS

Switzerland has rebooted its supercomputer network back into the global premier league of data processing. But who gets to use the sixth most powerful supercomputer in the world and what does it hope to achieve?

Mapping the universe, sorting health facts from conspiracy theories and more precise climate modelling are just some use cases for Switzerland’s Alps supercomputer. But there are no immediate plans to allow private companies to tap into its resources.

Switzerland’s previous supercomputer, Piz Diant, has been crunching numbers for scientific research projects since 2013. It has served, among others, the Swiss meteorological service, the federal materials testing institute and the Paul Scherrer Institute of engineering sciences.

Piz Diant has now been replaced by the Alps Supercomputer, which will have 20 times the computing power of its predecessor when fully operational and the muscle to exploit the potential of artificial intelligence (AI).

It’s also the world’s sixth most powerful computer, with only the United States, Finland and Japan having more powerful machines. This has restored Switzerland’s supercomputing capabilities compared to other countries, which had been lost when Piz Diant was overtaken by more powerful machines around the world.

Access limited to science projects

But this does not mean 20 times more researchers will have access to the powerful computing network, which stretches over three sites in Switzerland and one in Italy. Some 1,800 researchers took advantage of the Piz Diant supercomputer and, so far, 1,000 have signed up to the new Alps network.

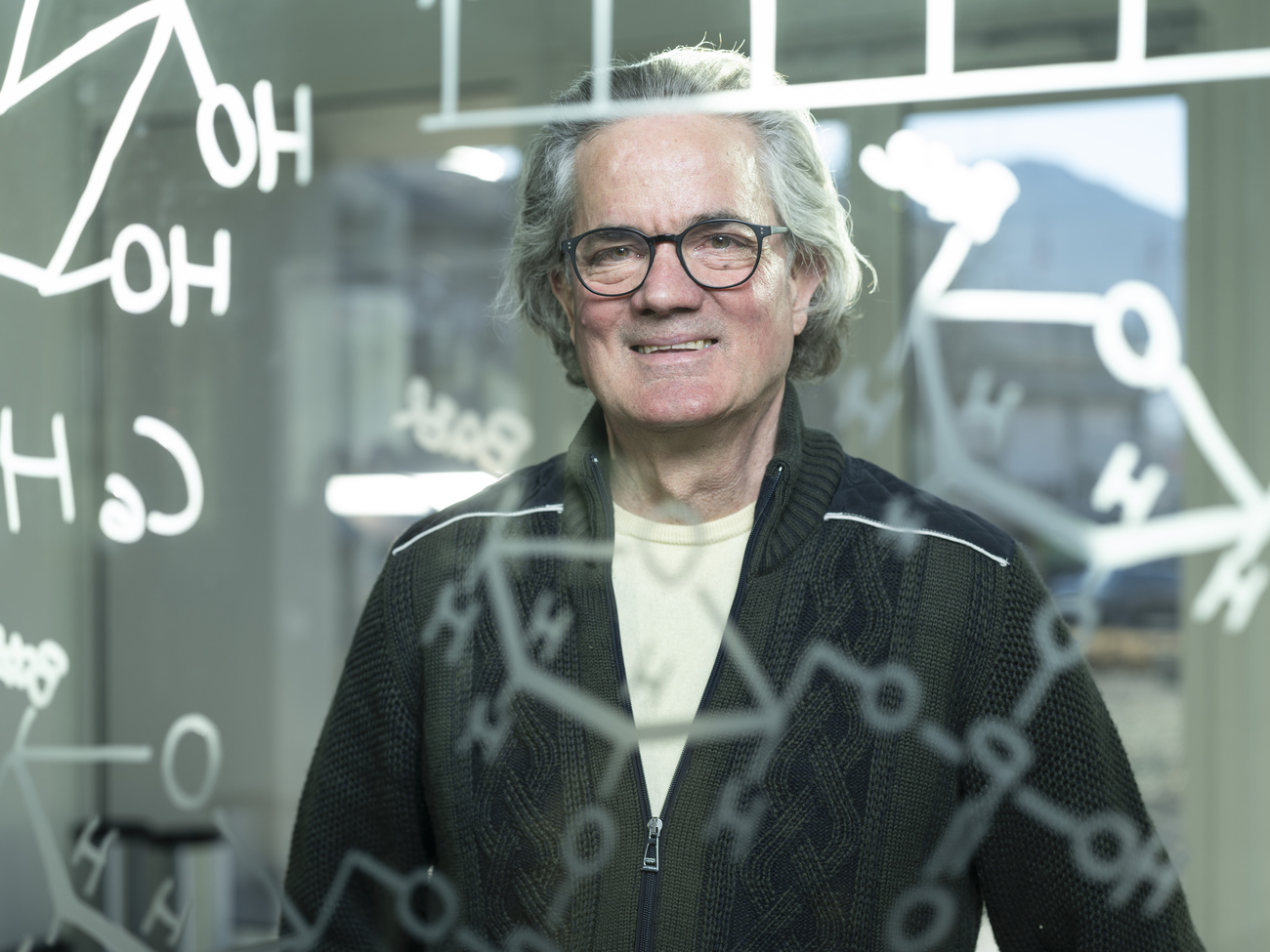

“We cannot serve a million researchers on this system,” Professor Thomas Schulthess, head of the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre (CSCS), told SWI swissinfo.ch. For a start, the CHF100 million ($118 million) supercomputer, with an annual operating budget pf CHF37 million, is funded out of the public purse. “We are a subsidised infrastructure, and subsidies don’t scale. We must be very disciplined in how the infrastructure is used,” said Schulthess.

The Alps supercomputer is not intended for mass commercial use. The extra computing power will instead continue to focus on Swiss and international research projects, mainly in the field of natural sciences.

Companies could apply for access if they collaborate with a Swiss university in their research and pay for the costs of using the supercomputer.

And as a part of the Swiss federal technology institutes, CSCS is obliged to grant three-year supercomputing access to so-called ‘spin-off’ companies, which commercialise university research projects into start-ups – provided they also pay their own way.

The association digitalswitzerland, which promotes digital innovation in Switzerland, says it is “exchanging with CSCS” on the topic of commercial access to the supercomputer, but would not give details on how these talks are evolving.

Securing data quality

Thomas Schulthess, head of the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre (CSCS).

Keystone / Gaetan Bally

There are other reasons, beyond the use of public funds, that explain why CSCS is not prepared to throw open the floodgates of wider access.

CSCS has an imperative to defend the quality of data on the supercomputer and prevent it from being compromised by projects with less rigorous filtering methods.

“In natural sciences we have methods to filter out bad data that have been known since the days of Galileo,” said Schulthess. “We want to help the humanities, commercial enterprise, and society to adopt these methods.”

This becomes critical in the age of AI as more powerful computers, hungry for data, are trained to process information by themselves. Inputting poor data into an AI system could cause it to reproduce biases and falsehoods with damaging consequences.

For example, Alps is being used to train the Meditron large language model (LLM) system that processes curated high quality medical data. Meditron is then used by doctors to make accurate diagnoses in countries where there is a lack of advanced medical infrastructure.

Harnessing quality data in this way could convince patients to choose evidence-based medical treatments ahead of dubious local remedies, said Mary-Anne Hartley, a professor at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL), who is part of the Meditron research team.

Sorting health facts from fiction

“Information is the ultimate determinant of health – and there is a lot of bad information out there,” she told an Alps conference in Zurich on September 13.

“In low-resource countries, there are no safety nets for patients. If we get something wrong, there will be serious consequences. We must follow the highest standards that are as robust as possible.”

The future impact of AI on computing science, and other disciplines, also makes it hard to predict which projects and institutions will use Alps ten years from now.

“The great unknown is how machine learning and artificial intelligence will develop,” said Schulthess. “AI could well bring about such changes that we have to find completely different methods of selecting and supporting new projects.”

Alps has been designed with flexibility in mind for researchers.

CSCS

Tailored software interfaces

To cope with a largely unpredictable future landscape, Alps has been designed with greater flexibility than its predecessor, Piz Diant. Alps is modelled to mimic a cloud system that allows researchers to plug in via software portals that are tailored to the specific needs of each project.

“In the past, high-performance computing (HPC) defined an environment that everyone had to adapt to. For the first time we can support several different environments by customising individual software interfaces to the needs of different research communities,” said Schulthess.

Projects already signed up to Alps include the Square Kilometre Array Observatory, which plans to map the universe in much greater detail using data extracted from thousands of radio antennae set up around the world.

Enhanced collaboration with Swiss and European meteorological services has the intention of producing more detailed and accurate climate forecasting models in future.

CSCS will retain its tested method for choosing which research it will support, which comprises a panel of international scientists to examine both the scientific integrity of projects and the readiness of candidates to carry out their tests on the supercomputer in the allotted time.

Large tech companies, such as Google and Amazon, have built their own supercomputers to support their research and business growth.

Alps, by contrast, will leverage AI to support scientific research.

“Science must assume a pioneering role in such a forward-looking field, rather than leaving it to a few multinational corporations,” said Vice-President for Research at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich (ETHZ), Christian Wolfrum, at the launch of the Swiss AI Initiative last December. “Only in this way can we guarantee independent research and Switzerland’s digital sovereignty.”

Edited by Veronica De Vore/ac